It has been written about Barbara Stanwyck, born Ruby Stevens, that she was an orphan.Her mother, Catherine Ann McPhee Stevens, Kitty, died in 1911, when Ruby was four years old. Following Kitty's death, Ruby's father, Byron E. Stevens, a mason, left his five children and set sail for the Panama Canal, determined to get away and hoping to find work at higher wages than at home.

Description:

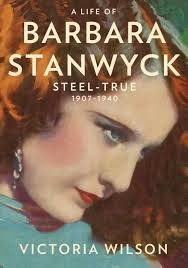

I just flat out love A Life of Barbara Stanwyck: Steel-True 1907-1940 by Victoria Wilson - all 860 pages of it. I also love the additional 140 pages of appendices, notes, index, and the 270 photos. There, I've said it.

Admittedly, I am a fan of Barbara Stanwyck, the noted film actress of Stella Dallas, So Big, and my favorite, Ball of Fire. (For you youngsters, she also won Emmys for roles on TV's Big Valley and The Thorn Birds miniseries and played a variety of roles in her career from hard core prisoner, gun moll, gold-digger, rancher, single mother, grifter, and bombshell).

Steel-True fills in the details of the first 34 years of Stanwyck's acting and private life; the complex, fascinating world of vaudeville, theater, and film; and the important actors, directors, writers, and family who created the era and contributed to her career. And all of it, and I really mean ALL of it, is fascinating for anyone even only slightly interested in stage, film, and life in Hollywood and New York during those formative years of entertainment.

Believe me, I never thought, even as a Stanwyck fan, I would be interested enough to conquer an 800-page biography. But this book is about more than just Barbara Stanwyck. It brings to life the world of stage and screen and the numerous factors that influence how a film or play is created. Author Wilson covers them all in a detailed, but concise description of these factors.

Just check out the book's first sentences quoted above. In under 70 words, author Wilson, a senior editor at Alfred Knopf publishing, introduces readers to the title character, her family, her given name, the loss of her mother at age 4, her father's profession, and his departure to Central America along with his reasons. Even gives her mother's nickname. It is impossible to cram more information into the first paragraphs but equally impossible to delete any of these details. Each is critical to the big picture of Stanwyck's life and therefore deserves a place in this book.

And it's equally impossible to stop reading since each paragraph also raise questions that need answering. "Wait, what? Stanwyck was an orphan?" "Who took care of her and her siblings?" "Did the father ever come back?" "Did they become a family again?" The next paragraphs answer those questions, but then raise new intrigues.

It's a self-perpetuating style: set the scene, explore the people and history behind the event, follow the actions that occur, describe the repercussions and then introduce the next setting and people that flow from the previous one. You cannot help but hunger for more details, resolution to situations, actions of principal people. You are teased to continue to read on and on and on until the book is completed. Each page makes readers feel like savvy insiders to each film, knowledgeable about the nuances that make a production rise or fall. We know the who, what, where, when, why, and how of each movie, every relationship, the stage and film industries, and the world at that time ... and we want to learn even more about the next production or item in her personal life.

The catalyst to all this historical detail is Barbara Stanwyck. By age 4 Stanwyck (born in Brooklyn as Ruby Stevens) had lost both her father (who left family to work on the Panama Canal) and her mother (in a freak trolley car accident), so spent her early childhood years shuttling between foster homes and her three older sisters.

One sister was a vaudeville performer who sometimes took Ruby to watch performances from the theatre wings. Soon Ruby is working on her own energetic dancing act, performing in the chorus for small clubs alongside 14-year-old Ruby Keeler and Mae Clarke. She eventually landed small jobs with musical revues on Broadway. By age 16, she was a "dancing cutie" in Keep Kool and the 1923 Ziegfeld Follies, earning $100 per week while learning about dancing, shows, men, and life. She also had a botched abortion in her early teens that left her unable to have children.

Her breakthrough performance came when Ruby, acting in a serious play as a background chorus girl with only a few lines, has her part expanded based on her voice and the magnetism she projected towards the audience. Her name is then changed by the producers to convey a more serious actress and "Barbara Stanwyck," a conglomeration of several current actors' names, was born. Her 1926 expanded role in The Noose attracted the attention of Hollywood and soon she was enticed to Hollywood during the age when silent films were first experimenting with talkies.

Stanwyck's lush, emotional stage voice, her strong work ethic, and the varied personalities she could convey to audiences, from triumphant to ferocious to sexy, made her a popular actress for a wide variety of roles, including gun molls, prison inmates, mothers, and gold diggers. Gradually, the parts became stronger, the scripts better, and her performances more nuanced, gaining starring parts with the most famous directors of the age: Frank Capra, William Wellman, King Vidor, Cecil B. DeMille, and Preston Sturgess.

From 1925 through the Depression years, she made $4,700 per week while other new actors made less than $40. After the successes of Night Nurse and The Miracle Woman, Stanwyck demanded $50,000 per picture, an astonishing salary for that era, making her the highest paid actress at that time. She had star power enough that she refused to be under contract with one studio as was the norm, allowing her the freedom to select her own movie roles, but also increasing her insecurity since no studio was obligated to provide roles for her. She also alienated film industry personnel by refusing to honor the screenwriters strike, continuing to make films when most other actors stopped working until writers received better pay. At one point she made 14 films in four years, including four with Capra.

But off the stage, her life was solitary. She was too shy and disinterested in the glitz of parties, choosing to spend nights at home quietly reading books rather than going out. Her marriage to Frank Faye, wildly-famous vaudeville emcee and comedian, was trying. He was the person who moved them to Hollywood when films beckoned him, but also introduced her to people who could start her with movie roles, and even financed one of her early films. His drinking, violent nature, controlling behavior, and disinterest in their adopted son strained Stanwyck's life. But she remained fiercely loyal. Even as her fame increased, she insisted on being referred to as "Mrs. Frank Faye" rather than her actress name. His abusive nature was the inspiration for the major character in the film, A Star Is Born.

Life became better for Stanwyck after her divorce from Faye and with her relationship with Robert Taylor, a $35-a-week pretty-boy newcomer to Hollywood and the leading man in one of her films. She helped him understand the nuances of roles, rehearsed his lines, created a stronger image of him, and turned him into the most popular actor of the 1930's. They had a long friendship which gave her new freedom, but she shied away from marriage. She felt:

Wilson extensively researched and interviewed many people from this era who knew Stanwyck as her contemporaries from the Vaudeville and early film era. Armed with this insider information, Wilson eagerly shares fascinating details about the people of that world, such as:

Can one person deserve1,000-pages? Of course not. But the era and people of Vaudeville, early Talkies, and later classic films around her do deserve such attention. This book is chock full of absolutely fascinating details, yet each is a brick necessary to contribute to the architecture of the world of stage, film, and the actress, Barbara Stanwyck. From her abandoned childhood, poverty, burlesque, stage, film, talkies, marriage, self-sufficiency and finally stardom, her story is marvelous to envision from the historical, theatrical, cinematic, and personal perspectives.

And remember, since Steel True only covers Stanwyck's life to 1940 (she died in 1990), there surely will be a Volume Two to cover her last fifty years. Probably (hopefully) it will be just as crammed with juicy, fascinating details as was Steel True.

I cannot wait.

Admittedly, I am a fan of Barbara Stanwyck, the noted film actress of Stella Dallas, So Big, and my favorite, Ball of Fire. (For you youngsters, she also won Emmys for roles on TV's Big Valley and The Thorn Birds miniseries and played a variety of roles in her career from hard core prisoner, gun moll, gold-digger, rancher, single mother, grifter, and bombshell).

Steel-True fills in the details of the first 34 years of Stanwyck's acting and private life; the complex, fascinating world of vaudeville, theater, and film; and the important actors, directors, writers, and family who created the era and contributed to her career. And all of it, and I really mean ALL of it, is fascinating for anyone even only slightly interested in stage, film, and life in Hollywood and New York during those formative years of entertainment.

Believe me, I never thought, even as a Stanwyck fan, I would be interested enough to conquer an 800-page biography. But this book is about more than just Barbara Stanwyck. It brings to life the world of stage and screen and the numerous factors that influence how a film or play is created. Author Wilson covers them all in a detailed, but concise description of these factors.

Just check out the book's first sentences quoted above. In under 70 words, author Wilson, a senior editor at Alfred Knopf publishing, introduces readers to the title character, her family, her given name, the loss of her mother at age 4, her father's profession, and his departure to Central America along with his reasons. Even gives her mother's nickname. It is impossible to cram more information into the first paragraphs but equally impossible to delete any of these details. Each is critical to the big picture of Stanwyck's life and therefore deserves a place in this book.

And it's equally impossible to stop reading since each paragraph also raise questions that need answering. "Wait, what? Stanwyck was an orphan?" "Who took care of her and her siblings?" "Did the father ever come back?" "Did they become a family again?" The next paragraphs answer those questions, but then raise new intrigues.

It's a self-perpetuating style: set the scene, explore the people and history behind the event, follow the actions that occur, describe the repercussions and then introduce the next setting and people that flow from the previous one. You cannot help but hunger for more details, resolution to situations, actions of principal people. You are teased to continue to read on and on and on until the book is completed. Each page makes readers feel like savvy insiders to each film, knowledgeable about the nuances that make a production rise or fall. We know the who, what, where, when, why, and how of each movie, every relationship, the stage and film industries, and the world at that time ... and we want to learn even more about the next production or item in her personal life.

One sister was a vaudeville performer who sometimes took Ruby to watch performances from the theatre wings. Soon Ruby is working on her own energetic dancing act, performing in the chorus for small clubs alongside 14-year-old Ruby Keeler and Mae Clarke. She eventually landed small jobs with musical revues on Broadway. By age 16, she was a "dancing cutie" in Keep Kool and the 1923 Ziegfeld Follies, earning $100 per week while learning about dancing, shows, men, and life. She also had a botched abortion in her early teens that left her unable to have children.

Her breakthrough performance came when Ruby, acting in a serious play as a background chorus girl with only a few lines, has her part expanded based on her voice and the magnetism she projected towards the audience. Her name is then changed by the producers to convey a more serious actress and "Barbara Stanwyck," a conglomeration of several current actors' names, was born. Her 1926 expanded role in The Noose attracted the attention of Hollywood and soon she was enticed to Hollywood during the age when silent films were first experimenting with talkies.

Stanwyck's lush, emotional stage voice, her strong work ethic, and the varied personalities she could convey to audiences, from triumphant to ferocious to sexy, made her a popular actress for a wide variety of roles, including gun molls, prison inmates, mothers, and gold diggers. Gradually, the parts became stronger, the scripts better, and her performances more nuanced, gaining starring parts with the most famous directors of the age: Frank Capra, William Wellman, King Vidor, Cecil B. DeMille, and Preston Sturgess.

From 1925 through the Depression years, she made $4,700 per week while other new actors made less than $40. After the successes of Night Nurse and The Miracle Woman, Stanwyck demanded $50,000 per picture, an astonishing salary for that era, making her the highest paid actress at that time. She had star power enough that she refused to be under contract with one studio as was the norm, allowing her the freedom to select her own movie roles, but also increasing her insecurity since no studio was obligated to provide roles for her. She also alienated film industry personnel by refusing to honor the screenwriters strike, continuing to make films when most other actors stopped working until writers received better pay. At one point she made 14 films in four years, including four with Capra.

But off the stage, her life was solitary. She was too shy and disinterested in the glitz of parties, choosing to spend nights at home quietly reading books rather than going out. Her marriage to Frank Faye, wildly-famous vaudeville emcee and comedian, was trying. He was the person who moved them to Hollywood when films beckoned him, but also introduced her to people who could start her with movie roles, and even financed one of her early films. His drinking, violent nature, controlling behavior, and disinterest in their adopted son strained Stanwyck's life. But she remained fiercely loyal. Even as her fame increased, she insisted on being referred to as "Mrs. Frank Faye" rather than her actress name. His abusive nature was the inspiration for the major character in the film, A Star Is Born.

Life became better for Stanwyck after her divorce from Faye and with her relationship with Robert Taylor, a $35-a-week pretty-boy newcomer to Hollywood and the leading man in one of her films. She helped him understand the nuances of roles, rehearsed his lines, created a stronger image of him, and turned him into the most popular actor of the 1930's. They had a long friendship which gave her new freedom, but she shied away from marriage. She felt:

Friendship was more powerful than love, that when one reached the heights of romantic love, there was no place to go but back, but with friendship there was a goal that could never be completely attained. It could be built upon by years of devotion, but it was always possible to intensity it; friendship grew with the years, while love can only lose....'If you could fall in love with your best friend I suppose such a marriage would come as close to perfection as marriage can come.With Taylor beside her she finally blossomed socially, attended parties, purchased a horse-breeding ranch with her agent, Zeppo Marx, and cultivated strong friendships with Clark Gable and Carole Lombard, Fred MacMurray, Joan Crawford, Jack Benny and Mary Livingston, Wallace Berry, and William Holden. Eventually, to alleviate the public's concern over her living with a man, she married Taylor and settled into life on the ranch and in Hollywood.

Wilson extensively researched and interviewed many people from this era who knew Stanwyck as her contemporaries from the Vaudeville and early film era. Armed with this insider information, Wilson eagerly shares fascinating details about the people of that world, such as:

- John Garfield - the premier star of silent films was unsuccessful in talkies not because his voice was poor (as is usually reported), but because he slugged Louis B. Mayer for a lewd remark Mayer made at Garfield's wedding to Greta Garbo (she did not show for the ceremony). After that Mayer, as head of the studio, only gave Garfield poor roles with inexperience directors who allowed Garfield to look bad and say ridiculous dialogue that made him appear a fool and lose the love of the public;

- William Holden - could walk "on his hands along the outer rail of Pasadena's suicide bridge with its 190-foot drop" but as a new actor was terrified during the first days of shooting "Golden Boy" with Stanwyck;

- Producer/Director Darryl Zanuck - felt Stanwyck "had no sex appeal." But Stanwyck felt his criticism "had more to do with how 'he couldn't catch me,' ... than it did her allure or her acting ability. 'He ran around the desk too slow'";

- Screenwriter (at that time) William Faulkner - wrote "beautiful speeches but impossible for an actor to perform";

- John Ford, director - When told by a producer he was three days behind schedule, he "ripped out ten pages from the script. 'Now we are three days ahead of schedule' he said and never shot the sequences'";

- Stanwyck - was an insomniac who read a book a day, subscribing to book clubs, looking for stories that would make good movies for her. She gave most books away after finishing them but did collected a large number of first editions

Can one person deserve1,000-pages? Of course not. But the era and people of Vaudeville, early Talkies, and later classic films around her do deserve such attention. This book is chock full of absolutely fascinating details, yet each is a brick necessary to contribute to the architecture of the world of stage, film, and the actress, Barbara Stanwyck. From her abandoned childhood, poverty, burlesque, stage, film, talkies, marriage, self-sufficiency and finally stardom, her story is marvelous to envision from the historical, theatrical, cinematic, and personal perspectives.

And remember, since Steel True only covers Stanwyck's life to 1940 (she died in 1990), there surely will be a Volume Two to cover her last fifty years. Probably (hopefully) it will be just as crammed with juicy, fascinating details as was Steel True.

I cannot wait.

If this book interests you, be sure to check out:

McCracken, Elizabeth. Niagara Falls All Over Again

Fictional memoir of one member of a two-man old time vaudeville comedy team similar to Laurel and Hardy, as they work individually and later together on their comedy act, achieving tremendous success in performances, but varying results in their personal relationships. Captivating, revealing, and tragic/funny on all levels.

Hammerstein, Oscar Andres. The Hammersteins: A Musical Theatre Family

Everything you could possibly want to know about the earliest days of theatre in America, starting with the first Oscar Hammerstein who established theatres all over New York, to his grandson who wrote the classic musicals such as Showboat, Oklahoma, The King and I, The Sound of Music and many more. Loaded with great photos of the era as well. Highly recommended. (Previously reviewed here.)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Add a comment or book recommendation.